The financial press in New York and London is forecasting imminent regime change and the collapse of the Chinese Communist Party!

The following FT op-ed reckons the 'Wuhan flu' is China's Chernobyl:

Xi Jinping faces China’s Chernobyl moment

The following FT op-ed reckons the 'Wuhan flu' is China's Chernobyl:

Xi Jinping faces China’s Chernobyl moment

Throughout Chinese history, the reign of an imperial line was believed to follow a pattern known as the dynastic cycle. A strong, unifying leader establishes an empire that would rise, flourish but eventually decline, lose the “mandate of heaven” and be overthrown by the next dynasty.

Similar to Europe’s “divine right of kings”, the mandate of heaven differed in that it did not unconditionally entitle an emperor to rule the Celestial Empire. While on the dragon throne, the “son of heaven” had total power over his subjects. But he did not have to be of noble birth and he could lose his heavenly mandate for being unworthy, unjust or plain incompetent. The right of the populace to rebel was implicitly guaranteed if the heavens were seen to be displeased. Natural disasters, famine, plague, invasion and even armed rebellion were all regarded as signs the mandate of heaven had been withdrawn.

After the powerful peasant emperor Mao Zedong won a civil war in 1949, the Chinese Communist party attempted to dispel such beliefs as unscientific superstition. Since taking power in 2012, President Xi Jinping has encouraged a revival of some ancient traditions and beliefs.

But he has studiously avoided mention of the dynastic cycle and the mandate of heaven, especially as traditional omens have piled up over the past year.

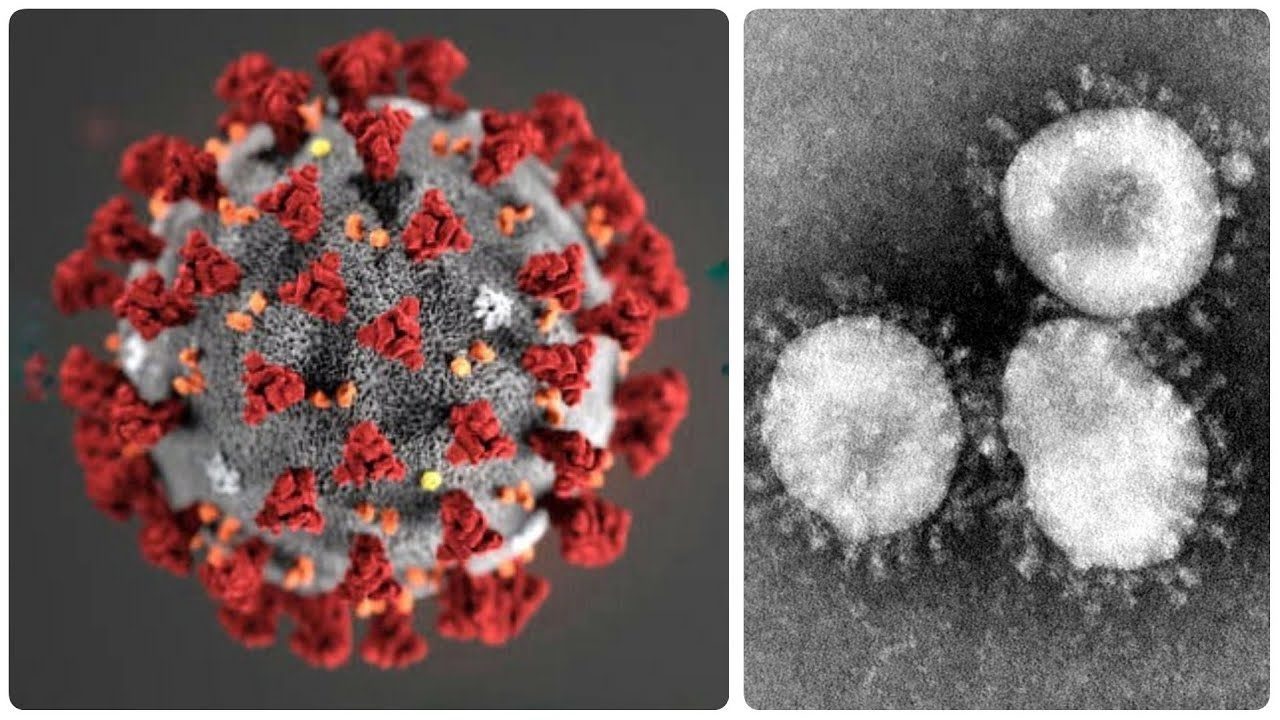

A trade war with China’s biggest trade partner, open rebellion in the former British colony of Hong Kong and pork shortages caused by the devastating spread of African swine fever would all be traditionally regarded as ominous portents that the end of the dynasty is near. But each of these pales in comparison to the unfolding coronavirus pandemic that began late last year in the central Chinese city of Wuhan.

In a twist of history, Wuhan was where the first shots were fired in the 1911 revolution that toppled the last emperor of the Qing dynasty. Today it is the source of a terrifying plague that has already spread across China and around the world and has prompted the biggest ever attempted quarantine of a population — some 60m people.

The fact that China’s authoritarian system is particularly poor at dealing with public health emergencies that require timely, transparent and accurate information makes this far more significant than any other challenge Mr Xi has faced so far.

If the virus can be contained in the coming weeks, then it is still possible Mr Xi could emerge relatively unscathed after blaming provincial officials for the crisis. Having shut down swaths of the economy to contain the outbreak, he may even be able to argue for greater surveillance and control of Chinese society. But if the virus cannot be contained quickly, this could turn out to be China’s Chernobyl moment, when the lies and absurdities of autocracy are laid bare for all to see.

Official censors are already struggling to control the online outpouring of derision and disgust at initial attempts to cover up the disease. One early target for ridicule was the senior health official sent from Beijing to Wuhan to publicly reassure the masses the disease was “preventable and controllable”. He contracted the virus himself and has become a symbol of government incompetence and mendacity.

Outspoken academics and intellectuals have braved imprisonment to lambast the Communist party’s failure of performance legitimacy. Some have explicitly referred to the mandate of heaven and pointed to numerous examples of late-stage dynastic decay. But the defining moment of this crisis — the moment when it went from being a serious challenge to a potentially existential problem for the party — was the death last week of a 33-year-old Wuhan ophthalmologist called Li Wenliang.

In the early days of the crisis, Li had raised the alarm in online chat groups with his medical school classmates after witnessing numerous cases of a strange new pneumonia that did not respond to normal treatment. For that he was reprimanded by his hospital and summoned in the middle of the night by the police, who forced him and at least seven other doctors to sign confessions and pledges to cease spreading “rumours”.

When Li contracted the disease himself, ordinary Chinese were outraged. Even the Supreme People’s Court in Beijing reprimanded the police and praised the doctors who first raised the alarm. But when Li died last week the response was volcanic.

The fact the news was released first by reporters from state media hints at cracks appearing in the fearsome party-controlled propaganda apparatus. Censors were unable to keep up with the outpouring of online demands such as “I want freedom of speech”.

Li’s story is so powerful in part because it fits neatly into another ancient archetype in Chinese history. The incorruptible Confucian scholar who speaks truth to the emperor but is persecuted, and ultimately dies for his honesty, holds a special place in China’s scholarly tradition. Li fits the role perfectly.

The path the virus takes next could determine whether Li is eventually compared to a more contemporary historic figure — the young Tunisian fruit-seller who immolated himself in protest at the injustice of the regime, sparking the Arab Spring and the downfall of several dynasties across the Middle East.