Natalie Renier/Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation is an important part of the Earth’s climate system. What if something disrupted it?

July 12, 2018 - Scientists may have solved a huge riddle that led to more than 1,000 years of cold on Earth. It doesn’t bode well

Scientists may have solved a huge riddle that led to more than 1,000 years of cold on Earth. It doesn’t bode well for the future. - The Boston Globe

Thirteen thousand years ago, an ice age was ending, the Earth was warming, the oceans were rising. Then something strange happened — the Northern Hemisphere suddenly became much colder, and stayed that way for more than a thousand years.

For some time, scientists have been debating how this major climatic event — called the

‘‘Younger Dryas’’ — happened. The question has grown more urgent: Its answer may involve the kind of fast-moving climate event that could occur again.

This week, a scientific team made a new claim to having found that answer.

On the basis of measurements taken off the northern coasts of Alaska and Canada in the Beaufort Sea, the scientists say they detected the signature of a huge glacial flood event that occurred around the same time.

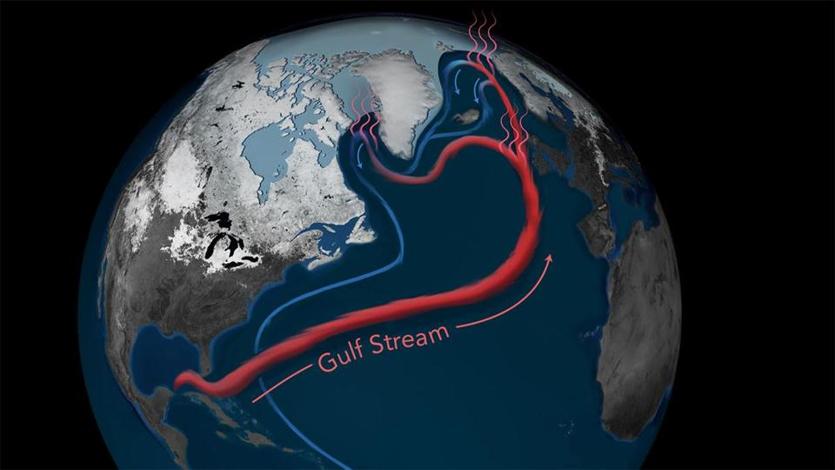

This flood, they posit, would have flowed from the Arctic into the Atlantic Ocean and shut down the crucial circulation known as the ‘‘Atlantic meridional overturning circulation’’ (or AMOC) — plunging Europe and much of North America back into cold conditions.

‘‘Even though we were in an overall warming period, this freshwater, exported from the Arctic, slowed down the vigor, efficiency of the meridional overturning, and potentially caused the cooling observed strongly in Europe,’’ said Neal Driscoll, one of the study’s authors and a professor at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

The work, published in Nature Geoscience, was led by Lloyd Keigwin of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution along with researchers at that institution, Scripps and Oregon State University.

The result remains contested, though, with other researchers still arguing for different theories of what caused the Younger Dryas - including a very differently routed flood event that would have entered the ocean thousands of miles away.

Nonetheless, the story is relevant because today, we’re watching another —or rather, a further — deglaciation, as humans cause a warming of the planet. There is also evidence that the Atlantic circulation is weakening again, although scientists certainly do not think a total shutoff is imminent, and are still debating the causes of what is being observed.

Either way, the new research underscores that as the Earth warms and its ice melts, major changes can happen in the oceans. And could happen again.

The researchers behind the current study, working on board the US Coast Guard Cutter Healy, analyzed sediments of deep ocean mud, which contain the shells of long-dead marine organisms called foraminifera. In those shells, the scientists detected a long-sought-after anomaly recorded in the language of oxygen atoms.

The shells contained a disproportionate volume of oxygen−16, a lighter form (or isotope) of the element that is found in high levels in glaciers. That is because oxygen−16, containing two fewer neutrons and therefore lighter than oxygen−18, evaporates more easily from the ocean but does not rain out again as readily. As a result, it often falls as snow at high latitudes and is stored in large bodies of ice.

‘‘This is the smoking gun for fingerprinting glacial lake outbursts,’’ Driscoll said. And that means the findings may also represent the trigger for the Younger Dryas.

The thinking is that as the ice age ended and the enormous Laurentide ice sheet atop North America began to retreat, the resulting meltwater fed a bevy of large lakes atop the depressed surface of the continent. That included the massive glacial Lake Agassiz, which stretched from the Great Lakes northwestward across much of Canada.

Prior research had shown that for a while, much of the resulting freshwater drained down the Mississippi River and into the Gulf of Mexico. But at some point, as the ice sheet continued to shrink, the flow of water appears to have been suddenly rerouted to the north or to the east, where it could do more potential damage to the ocean circulation in the Atlantic.

There has long been scientific debate about where all the meltwater actually entered the ocean, though, with some contending that it would have occurred through the St. Lawrence River, which flows past today’s Montreal and Quebec City and thus out into the Atlantic.

The new research holds that, instead, the floodwater exited through the Mackenzie River, which stretches across today’s Northwest Territories, emptying straight into the Arctic Ocean.

It would certainly have been an enormous flow of fresh water. ‘‘I would say somewhere between the Mississippi and the Amazon,’’ Keigwin said.

That could have interfered with the Atlantic circulation, which is crucial because it carries warm water northward, and so heats higher latitudes. Eventually, the waters of the circulation become very cold as they travel northward, but because they are also quite salty, they sink because of their high density and travel back south again.

Freshening is therefore the Achilles’ heel of the circulation. And the new study argues that although the glacial water would have entered the seas very far away near the present Alaska-Canada border, it would have then circulated around the Arctic, eventually traveling south past Greenland and entering the key regions that are crucial to the overturning circulation, which tend to be off Greenland’s southern coasts.

Not everyone is convinced, though - including some researchers who have previously published results suggesting that the outburst flood or flow was instead to the east, through the St. Lawrence River.

‘‘They have produced a nice signal of the release of freshwater into the Arctic Ocean, but the conclusions are based on an uncertain chronology which, when trying to tie together events so closely, requires some independent confirmation,’’ Peter Clark, an Oregon State University geoscientist who has published evidence supporting the St. Lawrence River theory, said in an email.

Anders Carlson, Clark’s co-author and colleague at Oregon State University, sent a geological study finding that, as he put it in an email, ‘‘the Lake Agassiz waters were clearly routed eastward at the start of the Younger Dryas.’’

‘‘This does not preclude Younger Dryas-age floods . . . to the Arctic Ocean,’’ Carlson wrote, ‘‘but it does show that such floods are of local origin and not related to the drainage of Lake Agassiz.’’

Both groups, though, think the flow of fresh water from the gigantic lake and from other melting events toward the Atlantic interfered with the ocean’s circulation — they’re just disagreeing about how it got there.

The question thus becomes whether it is possible to even more dramatically interfere with the circulation again — and what could cause that.

‘‘I don’t think there’s any lakes on land that are big enough to do this,’’ Keigwin said. ‘‘It has to come from ice, because that’s the biggest reservoir of freshwater. And Greenland is the ice mass that you would be most suspicious of, because it’s right there poised to do enough damage.’’

And yet, Greenland is no Lake Agassiz. ‘‘Greenland doesn’t have large land lakes to store the water,’’ Driscoll said. Rather, it releases steady streams of water in the form of glacial runoff, which often goes straight into the ocean — and it releases huge icebergs that slowly melt.

So nobody is necessarily expecting a sudden outburst flood as Greenland melts. Still, Driscoll and Keigwin both think that Greenland’s steady losses over time, especially if they increase in pace, can build up.

Climate scientists will be quick to point out that even if the Atlantic circulation slows or shuts down, ceasing to transport as much heat and leading to some Northern Hemisphere cooling, the overall global warming trend will still be ongoing and may overpower it. We won’t directly repeat the Younger Dryas, but we can learn from it.