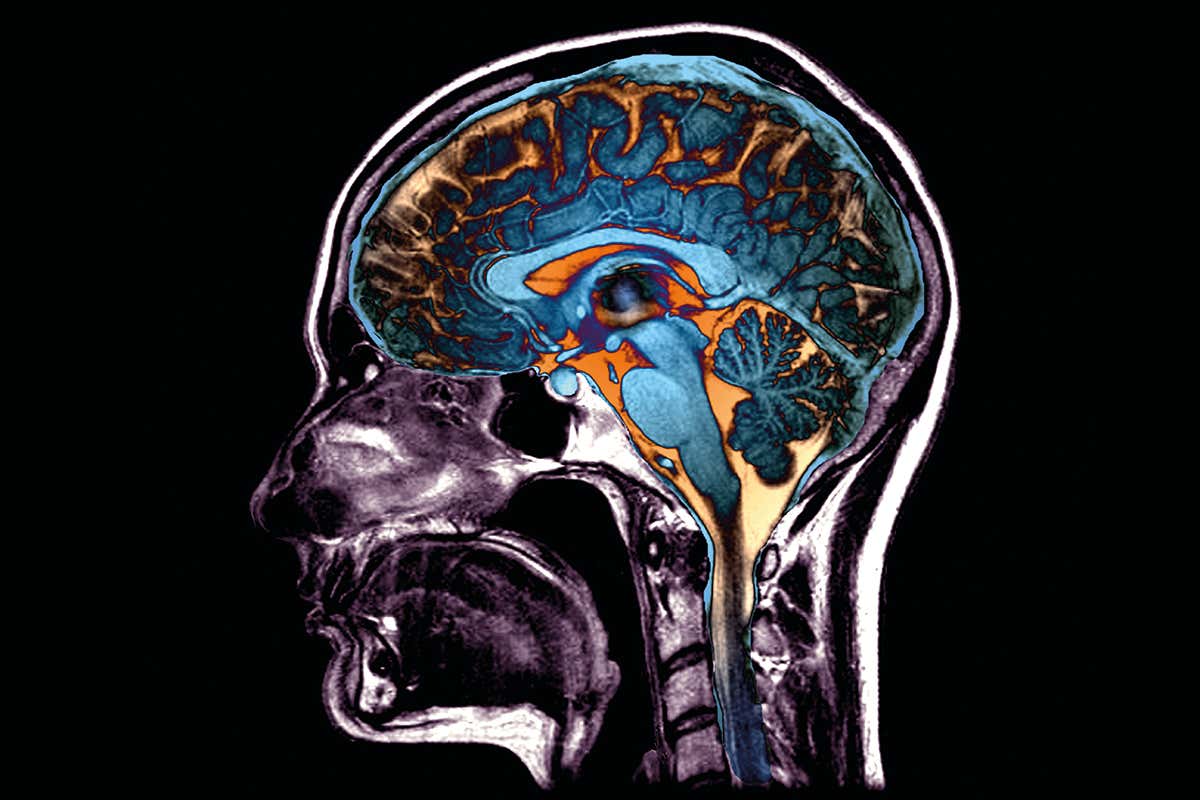

From loss of smell to stroke, people with covid-19 are reporting strange neurological issues that challenge our understanding of the disease – and how to treat it

JENNIFER FRONTERA has been treating people in intensive care for years. But she has never experienced anything like covid-19 before. “These patients are absolutely among the sickest any of us have ever encountered,” says the New York-based doctor. But the strange thing is, Frontera isn’t a lung disease specialist or a virologist, she is a neurologist. And it is the possible impact of the coronavirus on our brains that is worrying her.

It was early in the outbreak in New York that Frontera and her colleagues began to notice neurological symptoms in those with

covid-19. People were passing out before they were hospitalised. Once in hospital, some of them started having unusual movements. Some had seizures and others had strokes.

Similar reports are coming in from hospitals around the world. Some neurological symptoms appear to be mild, such as the loss of smell and taste. At the other end of the spectrum, a few people have developed encephalitis – a potentially fatal inflammation of the brain.

It is a surprising discovery in a disease that was generally considered to attack the airways, and one of pressing concern. One big question is how the new coronavirus is causing these kinds of symptoms. Growing evidence suggests that the virus may work its way into the brain, directly attacking neurons. If that is the case, we may need to reconsider some of the treatments being developed for covid-19. And we must also prepare for potential long-term and chronic neurological conditions in some survivors.

Millions of people globally have now been infected with the new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, but we are still learning

how it works. What we do know is that it can be spread by droplets from an infected person and seems to latch on to

receptors on cells in people’s airways.

That might be the end of the story for the many infected people who experience either mild symptoms or none at all.

But some will get very sick, showing flu-like symptoms that can progress to a severe pneumonia that leaves them struggling to breathe.

The official

symptoms listed by the World Health Organization (WHO) initially included fever, tiredness, dry cough, sore throat, shortness of breath, aches and pains and, sometimes, a runny nose or nausea or diarrhoea. But in response to growing reports of people losing their sense of taste and smell, the WHO and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have

expanded their lists of symptoms to include the loss of these senses. A

study of 214 people hospitalised with the virus in China has found that 5.6 per cent had a temporary loss of taste, while 5.1 per cent had a temporary

loss of smell.

Reports from Europe suggest that these symptoms may be more common.

A survey of 417 people treated at 12 hospitals across Belgium, France, Spain and Italy found that around 86 per cent experienced some change in their ability to smell, and 89 per cent had a “reduced or distorted” ability to taste flavours.

Other neurological symptoms are also showing up. Some people with covid-19 experience headaches and dizziness. Those with more severe illness can suffer seizures and strokes – even young people with no underlying conditions. Such outcomes are thought to be rare, although we don’t have exact numbers. An assessment of 214 people hospitalised with covid-19 in China found that around 6 per cent of those with severe disease developed a condition that affected blood supply to the brain. “We’ve seen strokes and bleeds in the brain,” says Frontera, who is based at NYU Langone Hospital – Brooklyn. There have also been a handful of reports of

brain inflammation and

brain damage in people with severe cases of covid-19.

In some diseases, neurological damage is a knock-on effect of other problems within the body, not caused by the pathogen attacking the nervous system directly. But in this case, it is also possible that the virus could be working its way into the brain and nervous system. Plenty of other viruses that infect humans do this, including coronaviruses.

Pierre Talbot at the National Institute of Scientific Research in Quebec, Canada, has been studying coronaviruses since the 1980s. Much of his work has focused on two

coronaviruses that are known to infect humans: HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-229E. Both often cause the common cold.

Finding a way in

We know that both can enter the nervous system and brain. “When I put [OC43] in the nose of mice, the virus goes straight to the brain through the olfactory nerve,” says Talbot. “And when it gets to the brain, it spreads to all areas of the brain.” Here, the virus can kill neurons and cause encephalitis.

Similar effects have been observed, but very rarely, in people infected with OC43. Talbot points to the case of an 11-month-old boy with a weak immune system who died with encephalitis. A biopsy revealed

OC43 in his brain, implicating the virus.

When Talbot and his colleagues

looked for 229E and OC43 in brain tissue from 90 people who donated their bodies to science, they found at least one of the two coronaviruses, and sometimes both, in almost half of the samples. Forty-four per cent of them had 229E in their brains and 23 per cent had OC43.

The SARS virus, another coronavirus similar to SARS-CoV-2, seems to act in similar ways.

The first SARS outbreak took place between 2002 and 2003, claiming about 8000 lives. Like the coronavirus that causes covid-19, the SARS virus also causes lung disease and can lead to fatal pneumonia in about 10 per cent of those infected. But autopsies performed after the outbreak ended revealed that the virus could get into the brain. In 2005, a team looked at eight people who died with SARS and

found the virus in all their brains.

And when researchers infected mice with SARS via their noses, they later found the virus in the animals’ brainstems. The brainstem sits between the brain and spinal cord and regulates our breathing. “You can imagine that could further worsen the respiratory failure of these patients,” says

Igor Koralnik at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, who studies diseases that infect the central nervous system.

What about the new coronavirus? A few reports claim to have found the virus in the cerebrospinal fluid of people with covid-19, which suggests it is getting into the brain and nervous system, says

Avindra Nath at the US National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

But there is a chance that the virus could get into a sample of this fluid without affecting the brain. If the virus is in a person’s blood, this might contaminate the sample taken during a spinal tap, for example.

It is also possible that neurological symptoms may be caused by a lack of oxygen. People who die with covid-19 have a lot of damage to their lungs. The surfaces of small air sacs become thickened, making it harder for oxygen to get into the blood, says Sanjay Mukhopadhyay at Cleveland Clinic in Ohio.

This may also explain why those who survive covid-19 after being treated on a ventilator can show signs of brain damage in scans, says Frontera. This damage is probably a result of the brain being starved of oxygen.

The body’s own immune response to an infection could also be to blame for damage to the brain. An overreaction of the immune system can lead to what is known as a

cytokine storm – an extreme activation of immune cells that can lead to more inflammation, and damage organs.

But based on the evidence we have so far, it is reasonable to assume the virus is getting into the brain, says Nath. If that is true, it is vital we learn how the virus is attacking the brain. “It will make a huge difference [to how we treat patients],” he says.

At the moment, many antiviral treatments being developed for covid-19 will focus on getting the medication to the lungs. Getting drugs to the brain is an entirely different challenge. For a start, any treatments will have to cross the blood-brain barrier – a protective layer in the brain that controls what can get in. Most drugs can’t do this. “It would be a totally different treatment approach,” says Nath.

“Based on the evidence we have, it looks as if the virus is entering the brain”

If the virus is accessing the brain, it could have long-term neurological consequences. We know that some viruses can hide in neurons, reactivating to cause disease later in life. Herpes simplex viruses, for example, typically cause cold sores or genital blisters. But in some people, they can trigger inflammation of the brain. Once a person has been infected, the virus lays low in their neurons and can reactivate throughout life.

“It’s not impossible that [the coronavirus] could have the same kind of persistence in the brain,” says Talbot. “We have seen OC43 and 229E in the brains of humans, and the virus seems to be hiding there – it’s possible that upon reactivation they could cause neurological disease.”

Some neurological effects are likely to have a lasting impact on people who recover from covid-19. Strokes and seizures can cause brain damage with long-term consequences, for example, and many of those who experience such outcomes will need follow-up care and rehabilitation.

The virus could also cause longer lasting secondary problems. Some might be in the form of

post-viral fatigue syndromes.

There is also concern about Guillain-Barré syndrome, which is characterised by poorly functioning peripheral nerves. “It’s like an ascending paralysis,” says Nath. “It starts with the feet and goes up.” Some cases are temporary, but other people experience lasting disability and it can even be fatal.

There is growing evidence that Guillain-Barré can develop in some people who recover from covid-19. So far, there have been reports of this in several countries. For example, across three hospitals in northern Italy, over a three-week period in March, doctors noted

five cases of Guillain-Barré out of between 1000 and 1200 people treated for covid-19. “That’s very significant. About a thousand times more than what you’d expect in the population [in the absence of covid-19],” says Koralnik. “We’re probably going to see many more such cases.”

It isn’t clear who is at risk of developing neurological symptoms or secondary disorders. But what is clear is that many people who are hospitalised with covid-19 and then recover will need to be followed up by healthcare providers, possibly for years.

Some of Frontera’s ventilated patients are already showing signs of severe brain damage. “The possibility of them waking up seems extremely low,” she says. The prospects for less severely affected people are still unclear. “We’re still learning about covid,” she says. “It will take a few months before we have a good idea of the prognosis.”

Apart from a temporary loss of smell and taste, most of the neurological effects seem to only occur in very severe cases of covid-19. Although we don’t yet have exact figures, it seems that only a very small fraction of people experience damage to their brain and nervous system. But it is possible that, for some people, brain effects will be lasting, says Nath. “Brain diseases can really affect who we are – they can change our personality, can affect the way we walk and move and cause all kinds of long-term consequences,” he says. “Even if it’s only in a small percentage of individuals, the devastation can be quite phenomenal. We should not take it lightly.”

Post-mortem problems

Autopsies on people who died after having covid-19 will help to clear up many of the questions about whether the coronavirus can enter the brain and what it does there (see main story). But so far, only a handful of these examinations have been performed. “A lot of autopsy suites are not equipped to handle this kind of infection,” says Avindra Nath at the US National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. “A lot of institutions have refused to do autopsies on these patients.”

And for those that are performing autopsies, getting hold of brain tissue can be particularly challenging, says

Desiree Marshall at the University of Washington, Seattle. “Removing the skull requires the use of a bone saw that produces aerosols [that could contain the virus],” she says. Such procedures should be performed in autopsy suites with special extraction systems that prevent air from passing to other rooms, and pathologists need adequate protective gear.

Marshall’s team has so far performed four brain exams of people who died with covid-19. Of those, one appears to show signs of damage, with very small bleeds on the surface of the brain and in the brainstem.

Direct effects?

Michael Osborn, who oversaw the development of mortuary services at the newly created Nightingale Hospital at London’s Excel Centre, has also been looking for post-mortem signs of damage inflicted by covid-19. So far, he and his team have performed full autopsies on six bodies. From these, they have discovered changes to blood vessels in the brain, which affect the amount of oxygen-rich blood that can get in. In these cases, brain tissue appears to have died because it hasn’t received enough oxygen. But it is difficult to know whether this is a direct effect of the virus reaching the brain or a consequence of breathing difficulties.

Both teams will be looking for the virus itself in brain tissue. But that won’t be easy, either. “Brain tissue takes a long time to process,” says Osborn. Together, these challenges mean that we still don’t know if the coronavirus is directly attacking brain cells. “We haven’t found virus in the brain yet, but I wouldn’t be surprised if other groups do,” says Marshall.

Organ impacts

Covid-19 is first and foremost a disease of the airways, causing severe harm in the lungs.

But doctors have been seeing signs of damage right across the body. While hospitals were attempting to increase the number of ventilators they had,

they were running out of dialysis equipment for covid-19 patients experiencing kidney failure.

Gastrointestinal problems have been seen too. And while many people are thought to die from a lack of oxygenated blood as a result of their breathing difficulties,

some of these people are in fact dying with multi-organ failure, such as damage to the heart and liver.

What is going on? It is possible that the virus behind covid-19 is reaching multiple organs by travelling through the bloodstream, says

Sanjay Mukhopadhyay, at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio. The virus is known to get into the lungs, which have a rich blood supply. “It’s very easy for these infections to get into the bloodstream,” he says. “Once the virus is in the blood, it can get to any organ.”

Whether the virus is directly damaging those organs is another question. Organ failure frequently results from serious illness, often as a result of the actions of the body’s own immune system. Ventilated people, struggling to get enough oxygen into their blood, are particularly at risk, says Mukhopadhyay. “When people develop that degree of severe lung injury, many other organs fail,” he says. “This is not unique to covid.” Pathologists including Mukhopadhyay, are now beginning to look for the presence of the virus in organs donated by people who died with the disease.

www.sbs.com.au

www.sbs.com.au

www.theage.com.au

www.theage.com.au

This is 10 days old "news" ....

This is 10 days old "news" ....

)

)