MH17 suspect Igor Girkin has been walking around freely for years.

5 years after MH17

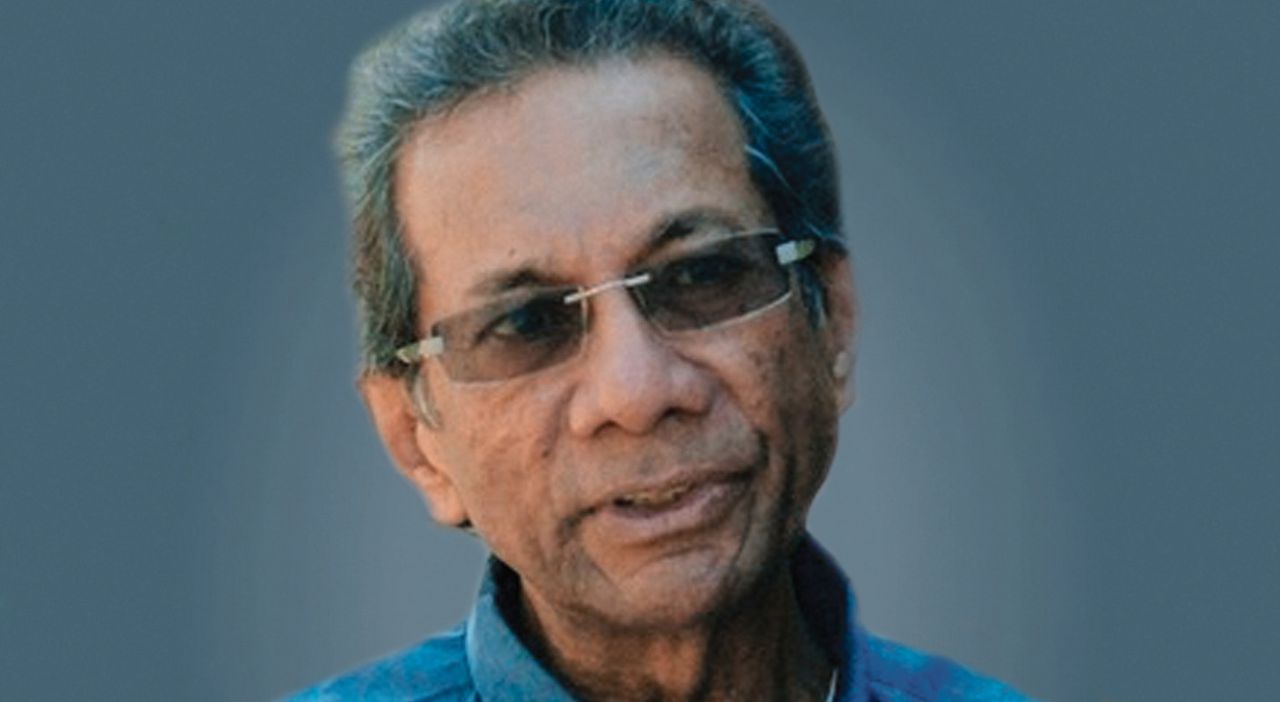

In Moscow he just walks down the street and is accosted by women who worship him. At the same time he is considered the most important suspect in the MH17 trial: former rebel leader Igor 'Strelkov' Girkin (48). This newspaper searched for the eccentric war fanatic and found him in Moscow.

Joost Bosman and Koen Voskuil < 13-07-19, 06:00 Last update: 09:45

On Wednesday evening 3 July,

Suvorov'skaya Square in Moscow is filled with left-wing nationalists, monarchists, Russian Orthodox and national bolsheviks. The peculiar group is demonstrating against plans for a large garbage dump outside the city.

While several speakers point out the garbage issue, a number of women in the audience have an eye for someone else. He has bright blue eyes and a thin mustache. He wears jeans and a light blue shirt, brown suede shoes and carries a leather shoulder bag. There is no doubt about it: right in front of the stage is the main suspect in the MH17 trial, Igor 'Strelkov' Girkin. Through the Russian social medium

VKontakte, he has called on people to come to the square to fight against the dumpsite. His fans are very excited when their war hero from the Crimea and the self-proclaimed People's Republic of Donetsk (DNR) in Eastern Ukraine appears among the public. He is immediately surrounded by middle-aged women.

Woman: "I love you and adore you. Give me your phone number!" Girkin: "Ho, ho. Give me your number." Woman: "Fantastic, you handsome! We keep fighting. I support Donetsk." Girkin: "So do I, madam. But there's nothing more I can do there at all. I can't even cross the border."

Uprising in Eastern Ukraine

Girkin does indeed have no business anymore in neighboring Ukraine, where insurgents in 2014 proclaim a People's Republic with the aim of joining Russia. The Joint Investigation Team (JIT), which is investigating the air disaster with MH17, wants to prosecute Girkin and has put him on the international investigation list. Because Russia does not extradite subjects, he is still safe in his hometown of Moscow.

When on July 17, 2014, a Russian rocket hit flight MH17, Igor Girkin led the uprising of pro-Russian rebels in Eastern Ukraine. A battle that continues to this day. As Minister of Defense in the DNR, he was responsible for bringing in the Russian anti-aircraft missile that put an end to 298 lives.

Woman next door

What brought this man to the battlefield of Eastern Ukraine? And how did he end up in such a high position? Discussions with family and friends of Girkin give an increasingly better picture.

Elena Konstantinovna (70) remains polite, but can't contain her criticism. What she should think of her old neighbor? She knows Igor Girkin from the past, as the son of well-educated parents, two floors higher. A slender boy, intelligent and already a bit out of the air. "When children were playing, he was on the sidelines. He didn't talk to them. Maybe he found himself smarter than others by then."

She formulates cautiously, but sometimes it is clear: Girkin should never have gone to Eastern Ukraine. "I didn't applaud that. Because he did it purely for himself. He only went there to fight, for the umpteenth time."

Not a family man

Konstantinovna in a purple robe is sitting in her kitchen on the seventh floor of an apartment building in

Bibirevo, a typical Soviet neighborhood in the north of Moscow: concrete flats with steel doors, where people already drunk in the morning roam around. Opposite the apartment on

Sjenskurski Avenue is his old primary school, a square building bordered by asphalt, grass and a fence of bars.

This is the apartment where Girkin returned to after his first marriage was over. With his second wife Vera he moved into the apartment opposite Konstantinovna. She hardly spoke to her old neighbor in all those years: he was always working. Although it is said that Girkin wrote two children's books, she does not know him as a children's friend. "He didn't even bother to look after his own sons."

Minister for Defense

In the spring of 2014, the family had suddenly left. Konstantinovna saw her neighbor on TV, as Minister of Defense of the People's Republic of Donetsk. He never visited his mother again, she says. "He has abandoned her. She's old, she misses him."

Two floors higher, mother Girkin doesn't react to the knocking on her door at first. Eventually a fragile old woman opens. When she hears that we are coming for her son, she pushes the door shut. "He's long gone here. You have to leave that boy alone", she says. "He hasn't done anything wrong."

War fanatic

That Girkin is attracted to war, his loved ones know ever since. He is a graduate historian and cherishes a love for historical battles. With a so-called re-enactment group he re-creates them, dressed in cossack uniform or medieval armor. He prefers to dress as a White Guard officer in the civil war of 1918-1920. Even his normal appearance, with short hair and striped mustache, was inspired by that time.

The war fanatic joined the Russian army after his studies and later becomes a reservist. Where fighting takes place, 'Strelkov' appears, 'the shooter' as his

nom de guerre reads. In the early nineties he fought in Bosnia as a volunteer on the side of the Serbs. There he would have met Aleksandr Borodaj, who five years later became the first Prime Minister of the rebels in Donetsk.

Russian secret service

The Russian human rights organization

Memorial is convinced that Girkin was partly responsible for the disappearance of six civilians during the Second Chechen War in 2001. The murders were allegedly carried out under the flag of the Russian secret service FSB, the successor of the KGB. Hacked e-mails from Girkin show that he worked there for years.

That Girkin in 2014 together with Borodaj played a role in the annexation of the Crimea peninsula and later on in Eastern Ukraine, is no coincidence. Both are former employees of the Russian Orthodox billionaire Konstantin Malofeyev who has been accused of financing the destabilization of Ukraine.

'Girkin is a maniac.'

In an English pub we talk to journalist Pavel Kanygin. He works for

Novaja Gazeta, one of the few Russian newspapers that dare to write that MH17 was shot out of the sky by a Russian BUK missile. According to Kanygin, Girkin also has personal motives to go to war. "He needs kicks all the time." Since 2001, six of Kanygin's colleagues have already been murdered. While he's telling his story, his eyes are scanning the cafe. Kanygin calls Girkin a narcissist. "He's a maniac."

As easy as others typify him, so taciturn is Girkin himself. As Defense Minister in Donetsk, between June and August 2014, he keeps journalists at bay. Only at occasional press conferences he wants to answer some questions, dressed in a camouflage shirt. The most eye-catching is his Stetsjkin pistol from the fifties, which dangles from his belt in a wooden holster. "A ridiculous weapon", says American correspondent Christopher Miller.

Slavjansk

Miller heard on July 5, 2014 that Girkin has lost an important city to the Ukrainian armed forces:

Slavjansk. He takes the first train to get there. Together with the journalists Noah Sneider and Max Seddon he walks straight to Girkin's former headquarters in an old office of the Ukrainian security service. They had heard rumors that journalists were locked up in the basement and wanted to investigate.

The building appears to be partly blown up and smells of smoke and gasoline. "Maybe Strelkov tried to destroy what he couldn't take with him." Under a thick layer of ash the three journalists find more than a hundred documents. When they read those documents, one of them stumbles upon execution orders. "We realized that this was important evidence," says Miller. Girkin appears to have signed three sentences from a rebel tribunal, in which four Ukrainians are sentenced to execution with a bullet. Among them is Alexej Pitsjko, a 30-year-old petty thief who had snatched two shirts and a pants from his neighbor's house. Pitsjko begs to be sent to the front. His wife is pregnant. But the 'chairman of the Court' inexorably pronounces the death penalty.

Antique gun

To justify the firing squad, Girkin uses a Soviet decree from 1941. "That crazy antique gun, that World War II decree: Girkin lives in the past," says Miller. "Don't forget that this man was re-enacting historical battles and lovingly would like to see the czar back in power." Girkin is considered an ardent supporter of the Great Russian Empire, and wants to make Russia a world power again. He believes that all Russian-speaking parts of the world should unite. For him, Ukraine is no more than a renegade province.

Loose cannon

Ideologically, Girkin clashes with the Kremlin, says Miller. "Girkin had imperialist visions in Donetsk. He thought he was building a Great Russia. But that has never been the goal of the Kremlin. They would trade that region for more political influence in the rest of Ukraine anytime. The Donbass is just a small pawn in the geopolitical game of Russia."

That game was thwarted when on 17 July 2014 flight MH17 was shot out of the sky. Girkin initially reacts triumphantly. On his account at

VKontakte he writes half an hour after the rocket impact that a cargo plane has been shot down: 'We warned not to fly in our airspace'.

Three weeks after the attack, which cost the lives of 298 people, Girkin is retrieved from Donetsk. "I suspect by the Kremlin", says journalist Pavel Kanygin. "All Russians in the top of the Donetsk People's Republic were quickly replaced by Ukrainians, to disguise the Russian involvement. In addition, Girkin was a loose cannon. I have heard that the Kremlin asked him in July to express his loyalty. He refused. That is his narcissistic side. He felt bigger than Putin."

Schizophrenic

An inflated ego is not the only problem according to Kanygin. "He suffers from schizophrenia. I have spoken several times with his ex-wife Vera. She says she has seen that on a medical certificate. In one of his children it has also been diagnosed. Because of that illness Girkin has not passed a psychological test of the FSB security service. That's why he had to leave."

Kanygin is convinced that Russia has knowingly sent a 'disturbed maniac' to Eastern Ukraine. "Clearly they couldn't send a regular Russian general, so they needed a mercenary with sufficient experience. And someone crazy enough to wage a dirty war there. The only problem with Girkin is that he doesn't take orders."

Political party

In August 2014 Girkin returned to Moscow bitterly. He makes several attempts to establish a political party against the regime of President Vladimir Putin. His

Russian National Movement, which did not get off the ground very well, pleads for the annexation of Ukraine, Belarus and other (partly) Russian-speaking states. The movement also calls for strict quotas for migrants.

The People's Republic of Donetsk is still of concern to him. He founds the

Novorossia movement, which supports the struggle in the Donbass with, among other things, aid supplies. However, his movement now no longer represents much. The income has dried up and Girkin has moved from an office in the center of Moscow to a small room in a suburb.

Novorossia

When we visit there, Eldar Khasanov, a member of the board of the movement, speaks to us. A camera is running during the interview, probably out of distrust of the Dutch journalists. Khasanov, who was a member of Girkin's general staff in the Donbass, puts blame on Russia for its unclear position on Eastern Ukraine. "This war has lasted longer than the Second World War. The same fascist ideology prevails in Ukraine as in those days. We have fought against this. It is an act of betrayal that Russia has let us down. Strelkov and I are disappointed about that."

Where Igor Girkin himself is staying at the moment is not clear from the conversation. Khasanov: "Strelkov is still the leader of this movement. That he does this says something about his character. He sincerely wants to help."

Garbage heap

Back to

Suvorov'skaya Square, where Girkin demonstrates against a garbage heap. He doesn't look happy when two Dutch journalists introduce themselves to him.

What are you doing here?

"I want to speak out for this non-political movement. It's important to every Russian that his country doesn't turn into a garbage dump."

How is your life in Moscow now?

"I live here pretty well."

We would like to ask you a few more questions, you know what they are about.

"When it comes to the Boeing, I do not comment at all, apart from what I have already said about it: the insurgents did not shoot the Boeing. That's final."

If you are not guilty, can you explain it?

"I told you that, didn't I? The insurgents did not shoot the Boeing. No further comment."

Who is to blame?

"I said: no comment at all."

Then the former rebel leader is boning off. His gaze is relaxed when he steps into a car. In his own Moscow he has nothing to fear.

Translated with

www.DeepL.com/Translator

As the saying goes: better late than never.

As the saying goes: better late than never.

a sweater while waiting for the evidence of which the The Editorial Board assures us is right in front of our faces, and then decries these are all "Moscow's crimes" and they must be guilty and charged in the court of 'law-abiding nations.' That's law-abiding nations, to repeat, in case there are any mirrors that reflect how good a job they are doing themselves.

a sweater while waiting for the evidence of which the The Editorial Board assures us is right in front of our faces, and then decries these are all "Moscow's crimes" and they must be guilty and charged in the court of 'law-abiding nations.' That's law-abiding nations, to repeat, in case there are any mirrors that reflect how good a job they are doing themselves.