So, it looks like these consulting firms are proxies used by the 'men behind the curtain' to steer the decision making around the globe, and both McKinsey and BCG are heavily promoting globalism and a 'digital society'.

Researching these firms, their history and various 'health projects' is a real can of worms, and a deep rabbit hole, and it would take a long time to get to know it all. However, for starters, below is a pretty good overview (on Vox, of all places!). It's a long article (haven't yet completed it), but it offers many very interesting clues:

The Gates Foundation brought billions of dollars to the sector — and a business-friendly ethos consultants could exploit.

www.vox.com

Thanks aragorn for posting,I had some burning questions that this article answers perfectly. I will include below some very interesting facts that came out of this article. We all need to be aware of the actions of these powerful players in global health.

, The US government and American NGOs ramped up their spending on global health —

so did American philanthropists, most notably Bill and Melinda Gates and Warren Buffett. Together, the trio formed the Gates Foundation, based on the belief that improvements in health (as well as education and development) could happen in low- and middle-income countries, with the help of science and technology. Since its inception in 2000, the foundation has given out more than

$50 billion

“WHO is faced with budget constraints,” McGoey said. “They’re under-resourced, and they need financing from somewhere. But they may have been a little naive in accepting a lot of Gates money, because it does come with strings attached.”

Those strings can involve hiring consultants, an ex-McKinsey consultant who worked on global health projects, said. As Gates began regularly paying for consultants on behalf of institutions like the WHO, it created a “reliance” on the firms. Then, the person said, “it became more of the norm to pull these same consultants in for strategy.”

During 2005-2006, global health activities at McKinsey consisted of 10 to 15 projects per year, according to the documents, and McKinsey hoped this would turn into 30 projects annually by 2009. Today, the firm’s “social sector” practice, however, includes among others, the

Global Public Health group, focused on advising “foundations, governments, bilateral and multilateral agencies, and healthcare companies” with projects in

35 countries.

Global health’s consulting dilemmas

The contributions of McKinsey and other consulting groups to global health are now being questioned, and they’re part of a larger conversation, mainstreamed by ex-McKinsey consultant and author Anand Giridharadas, about doing right by the world’s poor, trying to reduce wealth disparities, and saving lives efficiently and effectively. In conversations with more than 80 people who’ve worked in global health, including a dozen current and former consultants, these questions and concerns came up again and again:

This murkiness has frustrated the University of Edinburgh’s Sridhar, who has been trying to track the investments in management consultants for global health by international and philanthropic organizations.

“It’s an open secret in global health that all of this is happening,” she said. “[But] a lot of the information is not public or transparent. And it matters for accountability, transparency, and to ensure we can follow that the money is going to where it’s most needed.”

The fragments of public data we do have suggest it’s a staggering amount. In total, the Gates Foundation spent more than $300 million on McKinsey and BCG between 2006 and 2017, according to the foundation’s tax returns. That’s more than the domestic

health budget for an entire low-income country, like Haiti. It’s also roughly half of what the US government spent on

McKinsey and

BCG in the last decade.

When consultants’ advice flops in global public health, who is accountable?

The hundreds of millions spent on consultants, and lack of systematic evidence to support hiring them, is more concerning when you consider one feature that makes global health different from other areas: When consultants’ advice fails, it’s the lives of the poor and marginalized on the line. Or, in the case of McKinsey’s work with UNITAID, an organization funded mainly by public money, it was a high-profile

fundraising initiative for tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, and malaria in developing countries that failed.

Can consultants take credit for solving global health problems while also working for the industries that exacerbate them?

There’s an even deeper conflict between consultants’ private sector experiences and their public sector global health work: Their advice has been linked to some of the most urgent health crises of the last half-century.

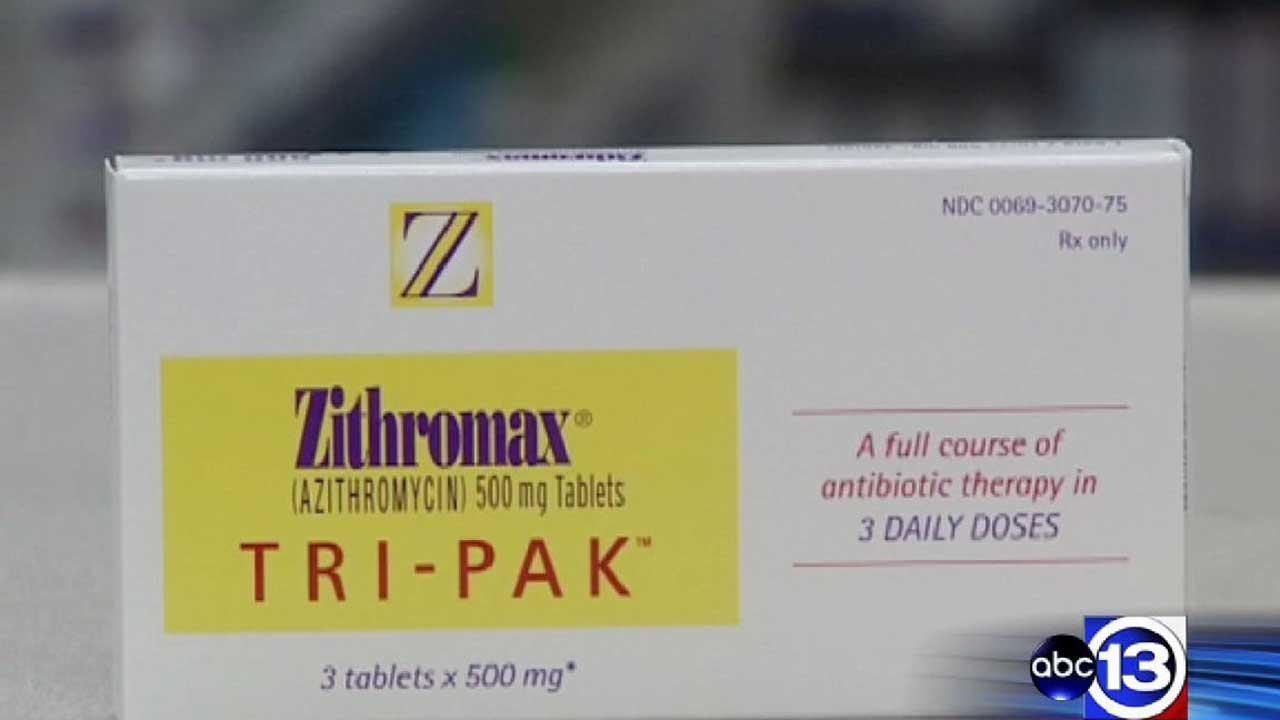

Consider McKinsey’s role in

the opioid epidemic, which has taken the lives of

nearly a million Americans since 1999. Court documents that surfaced in litigation included allegations that McKinsey advised two companies on how to increase sales of prescription opioids, from the early 2000s until at least 2014 — when the overdose epidemic was already well-known. One lawsuit alleged that McKinsey advised Johnson & Johnson to “get more patients on higher doses of opioids” and study techniques “for keeping patients on opioids longer,” the

New York Times reported.

Adam Kamradt-Scott, a professor in global health at the University of Sydney who studies the WHO, applauded its conflict-of-interest policies around tobacco. But he said despite “calls for the WHO to take a similar tough stand on the alcohol and sugar industries, we haven’t seen much progress in that yet.” He added,

“There is an inherent tension and conflict of interest if WHO is engaging consultancy firms that also work with companies whose products harm health outcomes.” (The WHO declined to comment.)

These conflicts are more apparent in a time when there’s greater scrutiny of how the winners of global capitalism are taking credit for reputedly solving the problems of the losers.

www.cnn.com

www.cnn.com

This article is very explainfull (if this is a word

This article is very explainfull (if this is a word