Transmarginal Inhibition

Wow! It’s been almost three weeks since I have written anything for my blog or SOTT! How time does fly! But, that doesn’t mean that I haven’t been writing; as it happens, I have. Not only am I working on the research for my upcoming book, “The Horns of Moses,” I have been working on our Cassiopedia project. After finishing the latest entry on Transmarginal Inhibition as researched by Ivan Pavlov, I thought that it was important enough to bring it to wider attention.

Pavlov demonstrated that when Transmarginal Inhibition began to take over a condition similar to hysteria manifested. In states of fear and excitement, normally sensible human beings will accept the most wildly improbably suggestions. |

Once you read this information, I think that you will agree with me that this is the process that has been used on the global masses for quite some time, with a peak of stress inducement on September 11, 2001. You will also understand why so many people have been hoodwinked. (By the way, you won’t find this kind of in-depth information on such subjects on Wikipedia!)

Transmarginal Inhibition

Transmarginal Inhibition, or TMI, is an organism’s response to overwhelming stimuli. Ironically, the popular acronym TMI means too much information, which can be a common factor of transmarginal inhibition in today’s culture.

Research

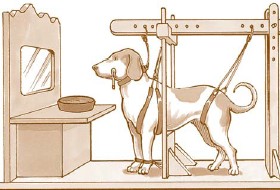

Ivan Pavlov enumerated details of TMI on his work of conditioning animals via various stimuli, including pain. (It is not true that all of Pavlov’s work was inducing responses via pain as is often reported.)

Pavlov discovered that an organism’s level of tolerance to various stimuli varied significantly depending on fundamental differences in temperament. He commented “that the most basic inherited difference among people was how soon they reached this shutdown point and that the quick-to-shut-down have a fundamentally different type of nervous system.” [1] This led him to pay increasing attention to the need to classify subjects according to their inherited constitution before applying experimental conditioning. Not only did dogs respond differently to conditioning according to their temperament, when a dog broke down under stress, its treatment depended on its constitutional type. For instance, Pavlov confirmed that sedatives were very helpful in restoring stability to the nerves of a dog that had broken down, but that the one type might require 5 to 8 times as much medication than that required by another type even if the body weight was exactly the same.

The Four Temperaments

Based on the empirical evidence accumulated through thirty years of research, Pavlov was convinced of the idea of the four basic temperaments. He noted that these temperaments approximated closely to those differentiated in man by Hippocrates. Though various blends of basic temperamental patterns appeared in Pavlov’s dogs, they could be distinguished as such instead of by creating new categories.

The first type corresponded with Hippocrates’s “choleric” type which Pavlov called “strong excitatory.” The second type: “sanguine” which Pavlov named “lively”, applied to dogs of a more balanced temperament. The normal response to imposed stresses or conflict situations by these two types was increased excitement and more aggressive behavior, but that is where the similarity ended. The “strong excitatory”, or choleric, type would turn so wild as to be completely out of hand as opposed to the “sanguine” type which continued to behave with purposeful and controlled reactions.

The phlegmatic type, Pavlov called “calm, imperturbable,” and the melancholic was called “weak inhibitory” type. In these two types, imposed stresses and conflict situations were met with more passivity or “inhibition” rather than aggression. The “weak inhibitory” type, or melancholic, constitutional tendency was to meet anxieties and conflicts with passivity and avoidance of tension. Any strong experimental stress imposed on such a dog’s nervous system resulted in the dog being reduced to a state of brain inhibition and “fear paralysis.”

Pavlov found that the other three types, when faced with more stress than could be coped with by the usual means, would also eventually enter a state of brain inhibition similar to that state entered very quickly by the melancholic/weak inhibitory type. He regarded this as a protective mechanism normally employed by the brain as a last resort when pressed beyond endurance. The “weak inhibitory” type was an exception to the other three types: this type of dog went into a state of protective brain inhibition more rapidly and in response to lighter stresses. The important finding was, of course, that the four basic natures responded differently to different levels of stress both before, during, and after experiments, the most important datum being that the weak inhibitory type was particularly susceptible.

Regarding the weak inhibitory type, Pavlov observed that though the basic temperamental pattern is inherited, every dog has been conditioned since birth by varied environmental influences which can produce long-lasting inhibitory patterns of behavior under certain stresses. Therefore, the final pattern of behavior of any given dog will depend on both its own constitution as well as specific patterns of behavior induced by prior environmental stresses. [2]

The Ultraboundary Response

Later, when Pavlov was experimentally applying his discoveries about dogs to human psychology, he noted carefully what happened when the higher nervous system of the dog was strained beyond the limits of normal response, and compared these states to clinical reports of various kinds of mental breakdowns in human beings. He found that more severe and prolonged stresses could be applied to dogs of the “lively” or “calm imperturbable” type without causing a breakdown, than to those of the “strong excitatory” and “weak inhibitory” types.

Pavlov was convinced that this “ultraboundary” response that he called Transmarginal Inhibition, was the brain’s protective mechanism. When it occurred, it meant that the brain had no other means of avoiding physical damage due to fatigue and nervous stress. He found that he could determine the degree of protective inhibition in any dog at any moment by using his salivary gland conditioned reflex protocol. Even if the dog seemed normal upon visual examination, the amount of saliva being secreted could tell him what was happening in the dog’s brain, i.e. whether the inhibitory response was initiating, and to what stage it had developed.

The Flood and Brainwashing

Apparently, an accidental event led to some of Pavlov’s more advanced experiments in induced TMI. In 1924, there was a flood in Leningrad. Pavlov had conditioned an entire group of dogs before this flood, during which they were trapped in their cages as the water rose steadily in the laboratory. The dogs were swimming around in terror, fighting to hold their heads above water when, at the last possible moment, a lab attendant came and pulled them down through the water and out of their cage doors to safety.

This event was evidently terrifying in the extreme to the dogs. Some of them switched from a state of acute excitement to severe Transmarginal Protective Inhibition. When Pavlov tested some of them soon after, he found that the recently implanted conditioned reflexes had all disappeared. Other dogs which had faced the ordeal were not affected. Pavlov realized that for those dogs whose conditioning had been wiped away by terror, there was a further degree of inhibitory activity that was capable of wiping the mental slate clean. Most dogs that had reached this stage of “brainwashing” could later have their old conditioned behaviors restored, but it took months of patient work. They were, effectively, “newborn”. If Pavlov would allow a trickle of water to run in under the door of the laboratory, all the dogs were sensitive to, and affected by, the sight; but most particularly those dogs who had been “brainwashed” by the flood.

Even though some of the dogs had resisted total breakdown, Pavlov was convinced that appropriate stresses “properly applied”, could have induced breakdown in every one of them. At the end of his life, Pavlov told an American physiologist that the observations made on this occasion had convinced him that every dog had its “breaking point”. [3]

Four Main Types of Stress

Among Pavlov’s most important findings was what can happen to conditioned behavior when the brain of a dog is pushed to the “ultraboundary” limit by stresses and conflict beyond its habitual response capacity. He was able to bring about what he called a “rupture in higher nervous activity” by utilizing four main types of imposed stresses.

1) The first type of stress was simply an increase in the intensity of the signal to which the dog was initially conditioned. If this was gradually increased, at a certain point, when the signal was too strong for its system, the dog would begin to break down.

2) The second way of achieving the ultraboundary event was to increase the time between the giving of the signal and the arrival of food. If a dog was conditioned to receive food five seconds after the warning signal, and this period was then prolonged, signs of restlessness and abnormal behavior would become evident in the less stable dogs. Pavlov discovered that the dog’s brains revolted against any abnormally long waiting period while under stress. Breakdown would occur when the dog had to either exert very strong, or very prolonged, inhibition. (Human beings also find protracted waiting while under stress to be debilitating: worse than the event that produces the anxiety.)

3) The third way of inducing a breakdown was to confuse the dogs by anomalies in the conditioning signal. If positive and negative signals were given one after the other, (yes, no, yes, no, etc), the hungry dog would become uncertain as to what would happen next and this disrupted the normal nerve stability. This is also true with human beings.

4) The fourth way of inducing a breakdown in a dog was to destabilize the dog’s physical condition in some way, either by subjecting it to long periods of work, inducing gastro-intestinal disorders, fever, disturbing the glandular balance, surgery, etc.

If, in any case, the first three methods would fail to induce a breakdown in a particular dog, it could be achieved by utilizing the same stresses that had failed, but doing so only after initiating the fourth protocol: physical destabilization. Pavlov also discovered that, after physical destabilization, a breakdown might occur even in temperamentally stable dogs and also that any new behavior pattern occurring afterward might become a fixed element of the dog’s personality even long after recovery from the debilitating experience.

In the weak inhibitory type of dog, new neurotic patterns implanted under such conditions could frequently be readily removed by little more than doses of sedatives. But in the calm and lively types – which often needed to be surgically castrated in order to physically debilitate them sufficiently to cause a breakdown – Pavlov discovered that the newly implanted pattern was quite often ineradicable after the dog had recovered its health. Pavlov thought that this was due to the natural toughness of the nervous systems in such types of dogs. The new behaviors were difficult to implant without temporarily induced debilitation and subsequently seemed to be as strong a part of the dog’s “stubborn nature” as the old pattern.

As observed by Pavlov, tolerence of stimulation varies greatly between individuals. Highly sensitive persons may be overstimulated by the loud volumes in a movie theater or the background confusion of a large social gathering. Other individuals will find those same stimulations as ideal stimulation levels, or even understimulating.

Three Stages of TMI

Pavlov established that the ability of a dog to resist heavy stress not only depended on its type, but its physical condition. Once the ultraboundary had been reached and cerebral inhibition induced, very strange things began to happen in the dog’s brain. These changes could be measured with some precision (by the amounts of saliva secreted), and, unlike with human beings, were not altered by subjective distortions. That is to say, there was no question of the dog trying to explain away or rationalize their odd behavior as human beings do. Three distinct and progressive stages of “ultraboundary” inhibition were described by Pavlov.

1)The Equivalent Phase of cortical brain activity. In this phase, all stimuli, of whatever strength resulted only in the same amounts of saliva being produced. In the human being, a similar phenomenon is observed when a normal person is in a state of extreme fatigue; they report that there is very little difference between their emotional reactions to either trivial or important experiences. They may say “I’m too tired to care.”

2) The Paradoxical Phase. When even stronger stresses are applied (and this can be pain or any other mental, physical, or emotional stress), the equivalent phase passes into the paradoxical phase. In this state, weak stimuli can produce a stronger reaction than a strong stimuli. The reason for this is that the strong stimuli only increase the state of protective inhibition while the weak stimuli can still produce positive responses. When a human being is in this stage, their behavior can reverse in a way that seems totally irrational to an outside observer.

3) The Ultra-Paradoxical Phase. The third stage is where positive conditioned responses suddenly reverse to negative responses and negative ones to positive. The dog (or person) may suddenly find that they like what they formerly detested and loathe what they formerly loved. In this stage, the organism’s response becomes opposed to all its previous conditioning.

Additional research on these phases was done by William Sargant in his work on shell-shocked servicemen.

Significance To Human Psychology

People are a lot like Pavlov’s dogs… |

This last discovery has great relevance to understanding similar changes in behavior in human beings. Toward the end of a long period of some type of debilitation, people of very strong character have been known to make a dramatic change in their beliefs and/or convictions. When they recover, they then are known to remain true to their new beliefs for the rest of their lives. There are many case histories of people who experience various types of conversion – religious, political, etc – during times of war, in prison, or after having some prolonged terrifying experience such as shipwreck, plane crash, etc.

Much of human behavior is the result of conditioned patterns of responses that begin to form in infancy and childhood. These patterns of response to reality can persist almost unchanged, but in general, the healthy adult human has learned to adapt their programs to changes in their environment. Other human responses are due to study and learning; driving a car, for example. In the beginning, learning to drive and negotiate in traffic requires a great deal of attention. Later on, it becomes more automatic and the driver can navigate in busy city traffic while talking, eating, or doing any number of other activities. “Driving” has become an automatic program. But if the driver then travels into the country where there is little traffic, he is able to adapt to changing conditions and does this automatically.

So it is that an organism’s brain is required to build ever more elaborate structures of both positive and negative conditioned responses – behavior patterns – to the changing conditions of the environment. Pavlov showed that the nervous system of a dog could develop extraordinary powers of discrimination automatically. A dog could be made to salivate in reaction to a tone of exactly 500 vibrations per minute, not 490 or 510.

Negative conditioned responses, such as anger or “fight or flight” reactions are generally controlled in civilized societies though it is occasionally necessary to activate them in response to changes in the environment such as threat or a life-or-death emergency.

The emotional attitudes and patterns of response are also conditioned in the human being though most people do not like to admit this. We learn as children to feel attraction or revulsion for certain things, people, events, and so on. Words such as “Catholic,” or “Communist” can evoke instant emotional reactions that have no relation to any facts or data, but are simply programmed attitudes acquired by conditioning within the family and society.

Use in Mind Control

The work of Ivan Pavlov was found by the Soviet totalitarian regime to be quite useful in pursuing their political policy of indoctrination. As evidence of this fact, it is noted that in July, 1950, a medical directive was issued in Russia for a re-orientation of all Soviet medicine along Pavlovian lines. [4] The reason for this directive is apparently due to the most impressive results that were obtained by applying Pavlovian principles.

Pavlov’s work seems to have strongly influenced the techniques used in Russia and China for the “eliciting of confessions”, for brainwashing and for inducing political conversions. This research has, apparently, been carried on in the U.S. by secret services who have a vested interest in “debunking” and marginalizing such information. Most of Pavlov’s findings applicable to Mind Control are reported in a series of Pavlov’s later lectures translated by Horsley Gantt, published in Great Britain and the United States in 1941 under the title “Conditioned Reflexes and Psychiatry.” [5] Professor Y. P. Frolov’s book about these experiments, Pavlov and His School [6] has also been translated into English. Later books made little or no reference to most of Pavlov’s important findings along the line of Mind Control. Joseph Wortis, M.D., in his study “Soviet Psychiatry”, published in the U.S. in 1950 [7], made a point to emphasize the importance of Pavlov’s experiments in psychiatry, but gave very few details of the last phase of this work that dealt with Mind Control. Other books contain many details of Pavlov’s early experimental work, but little to nothing of his later work relevant to Mind Control and brain-washing.

Pavlov demonstrated that when Transmarginal Inhibition began to take over a dog, a condition similar to hysteria in a human manifested. The applications of these findings to human psychology suggest that for a “conversion” to be effective, it is necessary to work on the subject’s emotions until s/he reaches an abnormal condition of fear, anger or exaltation. If such a state is maintained or intensified by any of various means, hysteria is the result. In a state of hysteria, a human being is abnormally suggestible and influences in the environment can cause one set of behavior patterns to be replaced by another without any need for persuasive indoctrination. In states of fear and excitement, normally sensible human beings will accept the most wildly improbably suggestions.

Social Implications

The means by which TMI operates on the individual is rather clear; what is less clear is how hysteria affects larger groups even moving to the macro-scale. Nevertheless, scientific observers of U.S. society since September 11, 2001, often point out that the events of that day were a classic example of inducing Transmarginal Inhibition in masses of people in order to condition them to accept the destruction of the U.S. Democratic government.

References

Frolov, Y.P. (1938). Pavlov and His School. Trans. by C.P. Dutt. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, London.

Babkin, B.P. (1951) Pavlov. A Biography. Gollancz, London.

Asratyan, E.A. (1953) I.P. Pavlov: His Life and Work (English translation) Foreign Languages Publishing House, Moscow.

Boakes, R. A. (1984). From Darwin to behaviourism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Firkin, B. G.; & Whitworth, J. A. (1987). Dictionary of Medical Eponyms. Parthenon Publishing. ISBN 1-85070-333-7

Pavlov, I. P. (1927). Conditioned Reflexes: An Investigation of the Physiological Activity of the Cerebral Cortex (translated by G. V. Anrep). London: Oxford University Press.

Todes, D. P. (1997). “Pavlov’s Physiological Factory,” Isis. Vol. 88. The History of Science Society, p. 205-246.

External links

Battle for the Mind by William Sargant

Brainwashing: Lecture Notes: Physiological Perspective

Nobel Prize website biography of I. P. Pavlov

Institute of Experimental Medicine article on Pavlov

Posted in Commentary, Conspiracy, NWO & Global Elite, Science