Jupiter, Nostradamus, Edgar Cayce, and the Return of the Mongols Part 8

The reader who has been following this little series of articles will notice that I have, at this point, slightly reorganized the material of the previous chapter and the present one. Thanks to all of you who wrote requesting more details on Iman Wilkens’ book and those who sent in additional clues which I am including here as well as maps scanned from the book.

Regarding Iman Wilkens book, Where Troy Once Stood, this book was recommended to me by a Welsh reader. I tried for some time to obtain a copy and, failing to do so, the reader kindly lent me one. I looked at the book, read the blurbs on it, and said to myself: “Yeah, right! What a bunch of hooey this is going to be!” However, since we had just recently moved house and our furniture and books had not arrived yet, I was pretty much left with no other book in the house but this one. With a lifelong habit of reading daily, you could almost say that I was “forced” to read it in spite of an a priori attitude of extreme skepticism.

I was prepared with my pen and notebook for the long list of criticisms I was going to write, but somehow, once I had started reading, the notebook never managed to fill up. Yes, there were things I thought could have been explained better if the author had been aware of the history of cataclysms and global climate changes on the planet during the periods he was concerned with, but for the most part, his approach and his logic were quite compelling, even if the evidence he collected was only circumstantial. Ancient history is a very difficult subject, but when so much evidence can be assembled to make a case, and a theory can be formed and tested successfully, then perhaps it is time to release “hardened categories” and long held beliefs in explanations that do not work.

As I have written elsewhere, historians of ancient times face two constant problems: the scarcity of evidence, and how to fit the evidence that IS known into the larger context of other evidence, not to mention the context of the time to which it belongs.

Fortunately, ancient history is not “static” in the sense that we can say we know all there is to know now simply because the subject is about the “past.” For example, the understanding of ancient history of our own fathers and grandfathers was, of necessity, more limited than our own due to the fact that much material has been discovered and has come to light in the past two or three generations through archaeology and other historical sciences.

Jews, Christians and Moslems have a certain notion of the past that is conveyed to them in hagiography, Bible stories, and the Koran, as well as in chronologies and historical accounts. We tend to accept all of these as “truth” – as chronological histories along with what else we know about history – and we often reject out-of-hand the idea that these may all be legends and myths that are meta-historical – special ways of speaking about events in a manner that rises above history. They may also be mythicized history that must be carefully examined in a special way in order to extract the historical probabilities.

The chronologies, the way that we arrange dates and the antecedents that we assume for events, should be of some considerable concern to everyone. If we can come to some reasonable idea of the REAL events, the “facts,” the data that make up our view of the world in which we live and our own place within it, then perhaps such facts about our history can explain why our theologies and values tell us, not what we believe, but WHY we believe what we do, and whether or not we ought really to discard those beliefs as “historical.”

One could say, of course, that all history is a lie. Whenever we recount events or stories about people and times that are not immediately present to us, we are simply creating a PROBABLE picture of the past or a “distant happening.” For most people, the horror and suffering of the Iraqi people, at the present moment in “time,” has no spatial meaning because it is “over there.” It is quite easy for false images of such events to be created and maintained as “history” by those who are not directly experiencing the events, particularly if they are not told the truth about them by those who DO know. And so it has been throughout history.

An additional problem is that history not only is generally distorted by the victors, it is then later “mythicized.” There is a story found in the History of Herodotus, which is an exact copy of an older tale of Indian origin except for the fact that in the original, it was an animal fable, and in Herodotus’ version, all the characters had become human. In every other detail, the stories are identical. Joscelyn Godwin quotes R. E. Meagher, professor of humanities and translator of Greek classics saying: “Clearly, if characters change species, they may change their names and practically anything else about themselves.”

Going further still, historian of religion, Mircea Eliade, clarifies for us the process of the “mythicization” of historical personages. Eliade describes how a Romanian folklorist recorded a ballad describing the death of a young man bewitched by a jealous mountain fairy on the eve of his marriage. The young man, under the influence of the fairy was driven off a cliff. The ballad of lament, sung by the fiance, was filled with “mythological allusions, a liturgical test of rustic beauty.”

The folklorist, having been told that the song concerned a tragedy of “long ago,” discovered that the fiance was still alive and went to interview her. To his surprise, he learned that the young man’s death had occurred less than 40 years before. He had slipped and fallen off a cliff; in reality, there was no mountain fairy involved.

Eliade notes that “despite the presence of the principal witness, a few years had sufficed to strip the event of all historical authenticity, to transform it into a legendary tale.” Even though the tragedy had happened to one of their contemporaries, the death of a young man soon to be married “had an occult meaning that could only be revealed by its identification with the category of myth.”

To the masses, hungry to create some meaning in their lives, the myth seemed truer, more pure, than the prosaic event, because “it made the real story yield a deeper and richer meaning, revealing a tragic destiny.” We could even suggest that George Bush is viewed in this way by many Americans who prefer to believe that he is a heroic president landing on aircraft carriers with verve and flair and a glint of steel in his eyes, protecting them from evil terrorists when in fact, he is a cheap liar, a psychopath, and undoubtedly complicit in cooking up the attack on the World Trade Center.

In the same way, a Yugoslavian epic poem celebrating a heroic figure of the fourteenth century, Marko Kraljevic, abolishes completely his historic identity, and his life story is “reconstructed in accordance with the norms of myth.” His mother is a Vila, a fairy, and so is his wife. He fights a three-headed dragon and kills it, fights with his brother and kills him, all in conformity with classical mythic themes.

The historic character of the persons celebrated in epic poetry is not in question, Eliade notes. “But their historicity does not long resist the corrosive action of mythicization.” A historic event, despite its importance, doesn’t remain in the popular consciousness or memory intact.

The memory of the collectivity is anhistorical. Murko Chadwick, and other investigators of sociological phenomena have brought out the role of the creative personality, of the “artist,” in the invention and development of epic poetry. They suggest that there are “artists” behind this activity, that there are people actively working to modify the memory of historical events. Such artists are either naturally or by training, psychological manipulation adepts. They fully understand that the masses think in “archetypal models.” The mass mind cannot accept what is prosaic and individual and preserves only what is exemplary. This reduction of events to categories and of individuals to archetypes, carried out by the consciousness of the masses of peoples functions in conformity with archaic ontology. We might say that – with the help of the artist/poet or psychological manipulator – popular memory is encouraged to give to the historical event a meaning that imitates an archetype and reproduces archetypal gestures.

At this point, as Eliade suggests, we must ask ourselves if the importance of archetypes for the consciousness of human beings, and the inability of popular memory to retainanything but archetypes, does not reveal to us something more than a resistance to history exhibited by traditional spirituality?

What could this “something more” be?

I would like to suggest that it is best explained by the saying: “the victors write the history.” This works because the lie is more acceptable to the masses since it generally produces what they would LIKE to believe rather than what is actually true. We have certainly seen a few hints that this is exactly what George Bush and company are doing, and based on this “rewriting of the event” in real time wherein Bush is scripted as the star of the show and the recipient of a “directive from God,” he has been able to further plans for world-domination utilizing a religion that clearly is no different from other cults with the exception that George Bush and cronies are the beneficiary.

Sounds a lot like what Stalin did in Russia, and what the CIA has been doing all over the planet since WW II and certainly what monotheism has been doing for the past two thousand years.

The fact is, manipulation of the mass consciousness is “standard operating procedure” for those in power. The priests of Judaism did it, Constantine did it, Mohammed did it, and the truth is, nothing has changed since those days except that the methods and abilities to manipulate the minds of the masses with “signs and wonders” has become high tech and global in concert with global communication.

Getting back to Where Troy Once Stood, Iman Wilkens did his homework in a very creative and open minded way. Among the things he examined in the Iliad and Odysseywere the sailing directions. Having a friend in the shipping industry who is a specialist in guidance systems, I asked him a number of questions about this process and he confirmed that Wilkens approach and conclusions were correct. He also concentrated on the geography and spatial locations of Homer’s world. Iman Wilkens tells us:

As work on Homer’s puzzle progressed, it turned out that many towns, islands and countries were not yet known in the eastern Mediterranean at the time of the Trojan War by the names mentioned by the poet.

Places like Thebes, Crete, Lesbos, Cyprus and Egypt had entirely different names in the Bronze Age, as we now know from archaeological research. The theatre of Homer’s epics can therefore never have been in the Mediterranean, just as, say an epic found in the United States about a Medieval war, mentioning European place-names (which can be found in both countries) could not have taken place there, as the American continent had not yet been discovered!

As to Homer’s place names, we are confronted with a similar problem but it is not really surprising that such a fundamental error in chronology could persist for some 2,700 years as traditional beliefs handed down over a long period are seldom challenged: each generation simply repeats the teachings of the previous one without asking itself the proper questions.

But now that this problem of timing has come to light, we are obliged to look for Homer’s places elsewhere than the eastern Mediterranean, and situated near the ocean and its tides, in particular where dykes prevented low-lying areas from flooding. In other words: we have to look for Homer’s places along the Atlantic coast.

The outcome of this research will be unsettling to many and I also realize from my own experience that it takes some time to get accustomed to the Bronze Age geography of Europe. The best way of adjusting is by reading Homer together with the explanations and maps of this book. Those who remain sceptical should realize that the problem of place-name chronology in general and the phenomenon of oceanic tides in particular, exclude any alternative solution. […]

At first sight it seems impossible to penetrate such a very distant past, but it turns out to be still feasible to discover what happened over 3,000 years ago, and precisely where, thanks to the branch of linguistics dealing with the history of word forms – etymology.

While the Greek spelling of Homer’s geographical names was fixed once and for all when the poems were written down … place names in western Europe went on changing in accordance with more or less well-established etymological rules, to be fixed by spelling only relatively recently.

Taking this fact into account, we shall see how virtually 400 odd Homeric place-names can be matched in a coherent and logical fashion with western European place-names as we know them today. Many of them are still easily recognizable, others very much less so, often because they have changed by invaders speaking a different language.

Even over the last few centuries, some place-names around the world have changed beyond recognition, due to pronunciation by peoples of different languages. Who, for example, would believe that Brooklyn in New York comes from the Dutch place name Breukelen, if it were not a documented fact?

While it is not possible to prove anything that occurred more than 3,000 years ago, I hope that my detective work has at least produced sufficient circumstantial evidence to convince the readers that the famous city of Troy was situated in western Europe. […]

The reason for the longevity of place names in general and river names in particular is that conquerors generally adopt the already-existing name, although often modified or adapted to their own tongue.

A major exception to this rule is Greece, where invaders arriving in a country almost emptied of its population gave new names to many places – names familiar to them and appearing in Homer’s works. But people arriving in a new and sparsely populated country of course give familiar names to places in a haphazard kind of way.

In Australia, for example, Cardiff, Gateshead, Hamilton, Jesmond, Stockton, Swansea, and Walsend, widely scattered in Britain, are all suburbs of Newcastle, New South Wales. It is precisely this haphazard transposition of names that explains, for example, why Rhodes is an island in Greece, but a region in Homer; Euboea is another Greek island, but part of the continent in Homer; Chios yet another island, but not in Homer. Similarly, Homer speaks of an island called Syria which clearly cannot be Syros in the Cyclades. The reader may object that these are simply imprecisions due to the extreme antiquity of the text. But we have evidence that the present Egypt, Cyprus, Lesbos and Crete, all names appearing in Homer, were not known by those names in the Bronze Age.

The list of such anomalies is long. Even the identification of such Homeric places as Ithaca and Pylos has led to endless and inconclusive discussion among scholars and the difficulty of making sense of Homer in Greece or Turkey is brought out in recent studies by Malcolm Wilcock and G.S. Kirk. It is therefore clear that the poet, though he uses names we recognize, was not talking about the places that now bear those names. [Where Troy Once Stood, Wilkens, p. 52-53]

Iman Wilkens cites the now very long list of reasons why Turkey is excluded as the site of Troy. (I’m not going to deal with those issues here; the reader may wish to pursue that line of research on their own.) Additionally, he points out the many reasons that support the location of the Troad in a country with a temperate climate, open to the Atlantic, and with tides. As Wilkens noted, considering the internal evidence of Homer’s works, it is only logical to look for the Troad in Europe, in a country formerly inhabited by the Celts, with an Atlantic climate, separated from the Continent by the sea, and having on its east coast a broad plain with a large bay capable of sheltering a big fleet of ships.

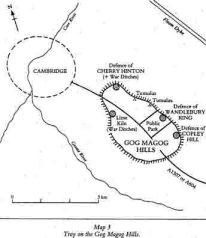

In England, there is, as it happens, an area corresponding perfectly to ALL of the descriptions in Homer – the East Anglian plain between the city of Cambridge and the Wash. Wilkens brings up a compelling argument:

Homer names no less than fourteen rivers in the region of Troy, eight of them being listed together in the passage where he describes how, after the Trojan War, the violence of these rivers in flood sweeps away the wood and stone rampart built round the Achaean encampment and the ships. It appears that generations of readers must have skipped over these lines, thinking they contained fictitious names of no interest, for otherwise, it is difficult to understand how nobody, not even people from the Cambridge area, was ever struck by the resemblance between the names of Homer’s rivers and those of this area.

Have a look at this list of river names, keeping in mind the several thousand years that have passed and that these changes are quite in line with phonetic changes according to the rules of etymology:

| Usual Rendering of the Greek River Name from Homer | Modern Name of the Corresponding River in England |

| Aesepus | Ise |

| Rhesus | Rhee |

| Rhodius | Roding |

| Granicus | Granta |

| Scamander | Cam |

| Simois | Great Ouse |

| Satniois | Little Ouse |

| Larisa | Lark |

| Caystrius or Cayster | Yare with Caister-on-sea and Caistor castle at the mouth |

| Thymbre | Thet |

| Caresus | Hiz |

| Heptaporus | Tove |

| Callicolone | Colne |

| Cilla | Chillesford |

| Temese | Thames |

As Wilkens notes, it is impossible to find these rivers in Turkey. All that can be found are four rivers that were later given Homeric names without regard to the geographical descriptions in the Iliad.

The evidence that the Trojan plain is the East Anglian plain is also backed up by Homer’s descriptions of the land: fertile soil, rich land, water meadows, flowering meadows, fine orchards, fields of corn, and many other details that perfectly describe England, but have absolutely no relationship to Turkey, either in modern or ancient times, as the archaeology demonstrates.

|

There still exists very substantial remains of two enormous earth ramparts, running parallel with one another, to the northeast of Cambridge, one twelve kilometers long and the other fifteen.

The ditches dug in front of the dykes are on the side facing inland, not towards the sea, which means that they were built by invaders, not defenders exactly as described by Homer. These are known today as Fleam Dyke and Devil’s Dyke.

As Wilkens notes, it is obvious that the invader who built these enormous defenses was planning on a long siege. Also, a very large army would have been needed to move the huge volume of earth that went into creating these dykes which are 20 meters high and 30 meters wide at the base. Therefore, it seems that the estimated number of combatants in the Achaean army – between 65,000 and 100,000 – might not be an exaggeration.

The two dykes are about 10 km apart, leaving room for the deployment of two large armies if the defenders were to breach the first rampart. A line drawn perpendicularly through the two dykes, extending inland, cuts through the highest hill in the Cambridge area now known as the Wandlebury Ring, part of a plateau called the Gog Magog Hills. Wilkens produces still another confirmation:

A second indication that Wandlebury was the site of Troy is provided by a further detail of Homer’s text, where he tells how the Trojan army, before the construction of the dykes, gathered on a small isolated hill before Troy:

Now there is before the city a steep mound afar out in the plain, with a clear space about it on this side and on that; this do men verily call Batieia, but the immortals call it the barrow of Myrine, [an Amazon] light of step. There on this day did the Trojans and their allies separate their companies. [Iliad, II, 811-815]

Some kilometers to the north of Wandlebury, there is indeed, an isolated hill where the village of Bottisham now stands. It seems permissible to associate the Homeric name of Batieia with that of Bottis(ham). […]

When Priam, with a herald, is on his way from Troy to the Achaean camp by the sea to ask Achilles to return the body of his son, Hector, they apparently follow the course of the Scamander and stop to water their horses at another place that is of great interest to us:

When the others had driven past the great barrow of Ilus, they halted the mules and the horses in the river to drink, for darkness was by now come down over the earth… [Iliad, XXIV, 349-351]

A modern map shows us that half way between where Troy was and the Achaean camp, on the river Cam, lies the small town of Ely, which very likely owes its name to Ilus, and ancestor of Priam and the founder of Troy. It may well be, therefore, that the great gothic cathedral of Ely was built on the site where Homer saw the tomb of the first Trojan king. [Wilkens]

According to the tale, after ten years of war and countless deaths, Troy was essentially wiped off the face of the earth. Obviously, everybody didn’t die but the silting of the Wash made it impossible to rebuild on the same site at that time, assuming that the survivors had the heart to do so. A new city was built on the Thames at Ilford, or the Ford of Ilium east of the present City of London. The Romans called this city Londinium Troia Nova, or “New Troy.” It was also known as Trinobantum, and the Celts called itCaer Troia, or “Town of Troy.”

Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote that New Troy was founded by Brutus in 1100 BC. That would certainly put the “real Trojan War” quite a bit earlier than most “experts” consider to be the appropriate temporal placement of this war. The Hon. R.C. Neville found glass objects from the eastern Mediterranean which were dated as being from the fifteenth century BC about 5 km from Wandlebury Ring. Objects of a similar date and origin have also been found in other parts of England, showing that there was trade between the Atlantic and Mediterranean peoples.

To suppose that the great cultures in the eastern Mediterranean area and in the Near East were separated from each other, in the beginning, by the broadest of gulfs, is an interpretation wholly at variance with the facts. On the contrary, it has been clearly enough established that we have to deal, in this region, with an original or basic if not uniform culture, so widely diffused that we may call it Afrasian.” [A. W. Persson]

There are two figures of the giants Gog and Magog that strike the hours on a clock at Dunstan-in-the West, Fleet Street, but few people in London seem to know why they are there. Adrian Gilbert writes in The New Jerusalem:

Once more we have to go back to Geoffrey of Monmouth’s book, in which there is a story of how, when Brutus and his Trojans arrived in Britain, they found the island sparsely inhabited by a race of giants. One of these, called Gogmagog, wrestled with a Trojan hero called Corineus and was eventually thrown to his death from a cliff-top called in consequence ‘Gogmagog’s Leap’.

In the 1811 translation into English of Brut Tysilio, a Welsh version of the chronicles translated by the Rev. Peter Roberts, there is a footnote suggesting that Gogmagog is a corrupted form of Cawr-Madog, meaning ‘Madog the great’ or ‘Madog the giant’ in Welsh. […]

In another version of the Gogmagog tale, the Recuyell des histories de Troye, Gog and Magog are two separate giants. In this story they are not killed but brought back as slaves by Brutus to his city of New Troy. Here they were to be employed as gatekeepers, opening and closing the great gates of the palace.

The story of Gog and Magog, the paired giants who worked the gates of London, was very popular in the middle ages and effigies of them were placed on the city gates at least as early as the reign of Henry VI. These were destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666, but so popular were they that new ones were made in 1708 and installed at the Guildhall. This pair of statues was destroyed in 1940 during the Blitz, the third great fire of London, when the roof and much of the interior furnishings of the Guildhall were burnt. A new pair of the statues was carved to replace them when the Guildhall was repaired after the war. [pp. 60-61]

In the above quote, we have a clue that the giants, Gog and Magog, were known to the people of England long before they had access to a Bible, so certainly the Gog Magog hills were not named after the war described by Ezekiel. Rather, Ezekiel must have known about the terrible conflict fought on the Gog Magog plateau.

The question that is often asked is: could there have been cities of as many as 100,000 inhabitants in England during the Bronze Age? The population definitely fluctuated over time, but archaeologists estimate a population of at least 3 million at the close of the Bronze Age. According to some experts, England was a populous country with well developed agriculture at that time. We read in the Iliad about orchards, vines and fields of corn.

About 2000 BC came Bell-beaker people, whose burials are in single graves, with individual grave-goods. The remarkable Wessex Culture of the Bronze Age which appears about 1500 BC is thought to be based on this tradition. The grave-goods there suggest the existence of a warrior aristocracy ‘with a graded series of obligations of service… through a military nobility down to the craftsmen and peasants’, as in the Homeric society. This is the sort of society which is described in the Irish sagas, and there is no reason why so early a date for the coming of the Celts should be impossible. …There are considerations of language and culture that rather tend to support it. [ M. Dillon and N. Chadwick, The Celtic Realms, Weidenfield and Nicolson, London, 1972]

If it is so that Troy was in England, then the first documented King of England was Priam – in the Bronze Age. It also explains why prehistoric spiral labyrinths engraved on rocks or laid out on the ground with stones are still called “Troy Towns” or “walls of Troy” in England, “Caerdroia” in Wales and “Trojaborgs” in Scandinavia.

There is more than a symbolic relationship between the spiral maze or labyrinths and the city of Troy. According to K. Kerenyi, the root of the word truare means “a circular movement around a stable centre.” Based on the archaeological evidence, the symbolism of the circular labyrinth is far older than Homer’s time, reaching back into the Stone Age.

Having discovered that there is good reason to believe the Troy was situated in England, we next must consider now the identification and locations of the Achaeans. As Wilkens has noted:

Places like Thebes, Crete, Lesbos, Cyprus and Egypt had entirely different names in the Bronze Age, as we now know from archaeological research. The theater of Homer’s epics can therefore never have been in the Mediterranean, just as, say an epic found in the United States about a Medieval war, mentioning European place-names (which can be found in both countries) could not have taken place there, as the American continent had not yet been discovered!

So, if the Egypt that we know was not Egypt at that time, where was it? Also, where was the land of the Achaeans?

If fourteen rivers in the same region of England correspond linguistically and geographically with those of the Trojan plain as described by Homer, the coincidence is so great that it cannot be accidental, and we must indeed be talking about the same plain. … At the end of the Iliad, Homer states explicitly where Troy was located, speaking through the voice of Achilles talking to the old King Priam, come to claim the body of his son, Hector:

And of thee, old sire, we hear that of old thou was blest; how of all that toward the sea Lesbos, the seat of Macar encloseth, and Phrygia in the upland, and the boundless Hellespont, over all these folk, men say, thou, old sire, was pre-eminent by reason of thy wealth and thy sons. [Iliad, XXIV, 543-546]

This does seem to delimit Priam’s kingdom fairly precisely, and these places are indeed now to be found in the Mediterranean. Lesbos is a Greek island off the Turkish coast, Phrygia is the high plateau of western Turkey and the Hellespont is the classical name for the Strait of the Dardanelles. It is precisely this description that inspired Schliemann to seek the ruins of Troy in a plain in northwest Turkey. [Wilkens]

Considering the fact that the archaeological evidence of the many levels of the “Troy” that Schliemann discovered simply do not support all the details of the story of the Trojan war, I agree with Wilkens that it seems that there was a general shift of Homeric place-names from western Europe to the Mediterranean after the end of the Bronze Age.

The sea upon which the Troad lay was called the Hellespont. This means the “Sea of Helle.” According to legend, Helle was a girl who fell from the back of a winged ram and drowned in the sea which was then named after her. She was the daughter of Athamas, King of Orchomenus and the sister of Phrixus.

The name Hel, or Helle is also written as El or Elle by those linguistic groups that do not pronounce the “H.” It is a word of very ancient Indo-European origin. Not only was El the name of the principal god of the pantheon of Ugarith, the ancient Syrian town on the Mediterranean, but “el” also means “god” in the Semitic languages.

The atlas of Europe contains so many place-names beginning with Hel, Helle, El and Elle that it is well worth having a look: (I apologize that the scan of the map is so difficult to read due to the contrast, but the idea can be gotten by having a look and then further examination of an atlas will provide additional evidence.)

Apart from the waters off the western tip of France, still called Chenal de la Helle, the name Hellespont or Helle Sea has disappeared from western Europe. But, there are good reasons to think that it must have been the name of the sea on the shores of which so many places named “Helle” remain. Also, there still remain an estuary in the Rhine delta called Hellegat, or “Gate to Helle,” while the origin of the name of the French resort of Houlgate on the Channel coast is undoubtedly Hellegat. The name of the port of Hull on the northeast coast of England comes from the word “hell” according to the Oxford dictionary of English Etymology. Additionally, the name of Broceliande, the vast forest of Paimpont in Brittany, known from the cycle of the Knights of the Round Table is “Bro-Hellean” in Armorican Breton, meaning “Land near Hell.”

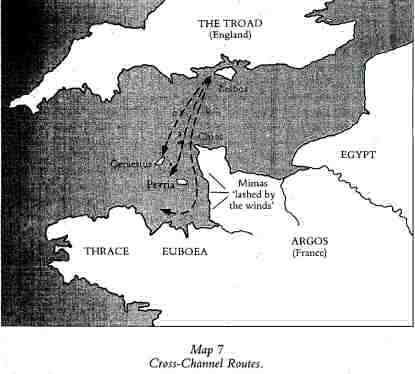

It therefore seems logical to conclude that Homer’s vast Hellespont was not the narrow strait of the Dardanelles in northwestern Turkey, but the sea separating England from the continent of Europe, in other words, the Channel, the North Sea and the Baltic, all the more so because the Greek adjective used to describe the Hellespont, apeiros, is much stronger than ‘vast’: it means ‘boundless’ which can only apply to the seas off the western shores of Europe, or, in other words, the Atlantic. [Wilkens]

Phrygia is the second frontier of the Troad mentioned by Homer and he describes it as an “upland.” We can look for the etymology of the word Phrygia in both the name of the Norse goddess Freya, and the name Phrixos, the brother of Helle. The name of the kingdom of their father was Orchomenus and there is, in fact, a place in west Scotland called Orchy, and on the north of Scotland there are the Orkney Islands, the archaic spelling of which is Orcheny. In the Orkneys, there is a town named Aith, the same as the name of Agamemnon’s horse. Following the principles of etymology, we even find the name of King Athamos preserved: Atham > Ethem > Eden> Edin > Edinburgh.

Many recent archaeological finds give evidence of big farms in Scotland dating as far back as 4000 BC, witness to an advanced culture that subsequently spread to the south of Great Britain.

Lesbos would then be the Isle of Wight. The name of the main river on the Isle of Wight is Medina, cognate with the Greek Methymna. The narrow strait separating the Isle from the mainland is called the Solent, related to the Greek noun solen which means channel or strait. Maps of the island show a promontory known as Egypt point.

According to Homer, Egypt is only a few days voyage from Troy. And so, if Troy was in England, Egypt must not be far away. Somewhere in western Europe there must be a region that subsequently gave its Bronze Age name to the land of the Pharaohs down south in Africa much later.

At the time of Homer, the land of the Pharaohs was not called Egypt, but Misr, Al-Khemor Kemi and often Meroë. This latter name applied to Upper Egypt and what is now called Ethiopia. The biblical name for Egypt was Mitsrayim which is still modern Hebrew for Egypt. Since its independence, the official Arabic name for Egypt has returned to Masr.

It was Herodotus, the first Greek to visit the pyramids who first called the Land of the Pharaohs by a name taken from Homer, Egypt. Alexander the Great made this the official name of the country in 332 BC. In other words, the Greeks did exactly what all colonialists do: they gave familiar names to places in their colonies and imposed their language on the peoples by virtue of making it the language of administration.

What is evident is that Homer’s description of Egypt does not at all match the features of the Land of the Pharaohs. This was noted by the Greek Philosopher Eratosthenes who lived in Alexandria. (284-192 BC)

Homer uses Egypt to designate a “river fed by the water of the sky” and sometimes the surrounding country with its “fine fields.” But he never, ever, mentions the pyramids which were, supposedly, already thousands of years old at the time of the Trojan War. Additionally, the pyramids are not mentioned by Aeschylus in his drama The Suppliants, the subject of which is the Druidic tradition from the north. He tells us how the suppliants, a group of fifty young women who wish to escape forced marriages, flee Egypt “across the salty waves to reach the land of Argos.” Later in the play, he writes how the young Io, pursued by a gadfly, returns from Argos to Egypt and “arrived in the holy land of Zeus, rich in fruits of all sorts, in the meadows fed by the melting snow and assailed by the fury of Typhon, on the banks of the Nile whose waters are always pure.”

Doesn’t sound much like Egypt, does it?

As those of you who have studied geography realize, Argos has never been part of, or near to, Egypt as we now know it. Furthermore, Egypt – as we now know it – was the land of Ra, the Sun God and, in ancient Egypt, Zeus was completely unknown. Finally, meadows watered by melting snow never, in any way, could describe the land we now know as Egypt.

So, since the Egypt described by both Homer and Aeschylus do not fit the Egypt we now know, and we don’t think they would have forgotten to mention the chief feature of Egypt – the pyramids – we must conclude that they were not talking about the Egypt we know as Egypt today.

Zeus was certainly known to France to the extent that one day of the week, Jeudi, or Thursday, comes from his name. It is the right distance from Troy, but, as Wilkens points out, we don’t find much etymologically speaking, to support the idea that Egypt was France. However, there are a few clues.

As it happens, there is a town and branch of the Nile in present day Egypt that the Greeks called Bolbitiron and Bobitinon. Correspondingly, there is a town called Bolbec near the mouth of the Seine. Then, there is a river in France called the Epte. This river flows from the north to join the Seine near Vernoin, half-way between Paris and Rouen.

There are many etymological artifacts of the name of the Nile in France where many villages contain -nil- (French for Nile) in their names. There is Mesnil, near Le Havre which, in twelfth-century church Latin was called “mas-nilii” or “house in the Nile country.. Then there is Miromesnil, Ormesnil, Frichemesnil, Longmesnil, Vilmesnil, and so on. Menilmontant, or “house on the upper Nile” is a district in Paris, and there is a suburb called Blanc-Mesnil. The god of the Nile had a daughter called Europe whose name is preserved in the river Eure, a southern confluent of the Seine.

At the time of the Pharoahs, in what we now know as Egypt, the Nile was called Ar or Aur. During the periods when it flooded, it was called Hape the Great.

Homer mentions a town in Egypt, Thebes, which cannot be the same town we know in Egypt which was, during the time of the Pharaohs known as Wase or Wo-se. It was only eight centuries after Homer that the Greeks gave it the new name of Thebes.

Utilizing the principles of etymology, Wilkens suggests that Homer’s Thebes is now called Dieppe.

According to etymological dictionaries the ‘d’ was formerly pronounced ‘t’ and the name is connected with the Germanic tief (English ‘deep’) for the harbour lies deep in the country. Let us recall that Homer, who always chose sound and concise descriptions, speaks of a country of ‘fair fields’ and a ‘heaven fed’ river. Dieppe’s hinterland is a beautiful farming region and the rain is never far awary in this part of France. What is more, recent archeological research has revealed that large farms existed in many parts of France in the Celtic period, so well-kept fields were a feature of the countryside even in that remote era. […]

The initial evidence found so far is thus in favour of identifying the Bronze Age Egypt as corresponding approximately to the present department of Seine-Maritime. [Wilkens]

Posted in Jupiter Nostradamus Edgar Cayce and the Return of the Mongols